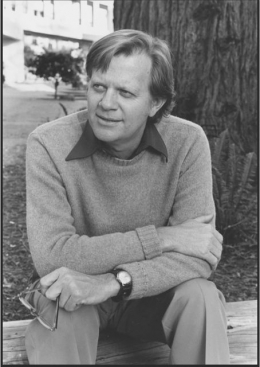

Professor Hayden White165 pages

Professor Hayden White165 pages

2013

For the full text [PDF] of Hayden White: Frontiers of Consciousness at UCSC (E-Scholarship) Includes complete audio (streaming or download) for the oral history.Note: Due to editing by the narrator and the Project, there may be minor differences between the audio recording and the transcript. Please quote from the transcript as the record and not the audio. Audio will be found under "Supporting Material."

Hayden White was born in Martin, Tennessee in 1928. During the Depression he moved with his family to Detroit in search of work, where his father became a union organizer in the automotive world. This urban scene of workers’ struggles to organize in the face of sometimes-violent corporate opposition was a watershed moment in informing White’s political consciousness.

After a stint in the military, he used the GI Bill to go to Wayne State University. White went on to graduate school at the University of Michigan. Dr. White spent a full twenty-three years teaching at other institutions before 1978, when he found a fertile space for his interdisciplinary conception of scholarly work as the chair of the University of California Santa Cruz’s History of Consciousness program.

In this oral history, White relates that history of consciousness gradually came to occupy a shifting territory that ranged from deep in the artistic side of the humanities well into the social sciences, and served as a haven for people interested in studying unconventional or cutting edge topics that weren’t at home in disciplinary graduate programs. The program actively recruited both gay students and students of color, seeking traditionally devalued perspectives, and ultimately, according to White, had a higher percentage of non-white students than any other humanities doctoral program anywhere. By late 80s and early 90s it was one of the most renowned humanities Ph.D. programs in the country, with an annual acceptance rate of five to six students for three to four hundred applicants. In a field where competing private schools and more well-funded public schools could offer big fellowships, histcon students had little to no fellowship money, but in spite of this fiscal obstacle the program built an international reputation, and had an unusually high rate of post-degree job placement for its students. In these interviews, White candidly charts the personalities and ideas and debates that gave shape and direction to this flagship humanities program, including those perspectives that changed the program—and him personally—in ways he hadn’t anticipated, like feminist studies and cultural studies.

In these sessions White discusses not just histcon and UCSC, but illuminates their broader contexts, discussing at length the fiscally slashed state of the humanities, the changing academic scene and wider geopolitical issues. More personally, he reflects on his philosophies on teaching, which he terms “a nobler designation,” and discusses his own writing and the historiographical subject matter that has inspired so much of his work. These interviews provide a vehicle for White to track the relationship of metahistory (the subject of his landmark book of the same name) to history, and explain his conception of moral relativism and different means of interacting with the past.

Santa Cruz, CA

Santa Cruz, CA